How Stephen King Made Pop Culture Weird

If you’ve ever been to Austin, TX, you’ve seen the bumper stickers: “Keep Austin Weird.” Even my new hometown of Tacoma, WA, likes to call itself weird, as does Portland, OR, in the photo above.

Lincoln Michel explains that these are not isolated occurrences:

If you haven’t heard, “weird” is back in style. From hit TV shows like Stranger Things and True Detective (season one only, please) to best-selling novels like Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach Trilogy and George R.R. Martin’s weirder-than-the-show A Song of Ice and Fire, pop culture is getting increasingly strange. Odd beasts, dark tunnels, and writhing tentacles are cool again. And, in the wake of his 69th birthday, it seems time to celebrate the person who is the most responsible for weirding up pop culture: Stephen King.

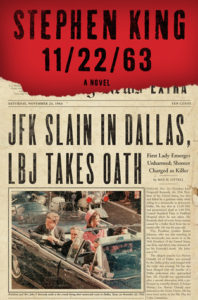

He singles out King because “Plenty of authors write books that are equally dark, weird, and genre-bending, but few have King’s impact on pop culture.” This article caught my eye because one of my recent reads was King’s 11/22/63, a time-travel alternate-history romance (“genre-bending,” although “genre-blending” would be more accurate) that kept me spellbound.

A theory of creepiness

If you’ve been hanging out around Notes in the Margin for a while, you’ve heard me say that I don’t read books about zombies, vampires, or werewolves. Even though I know these unnatural beings can be potent metaphors for contemporary life, I just don’t like them.

But, until I came across this article, I had never examined my revulsion with these creatures until I came across this article, which made me realize I dislike zombies, vampires, and werewolves because of their creepiness:

creepiness – Unheimlichkeit, as Sigmund Freud called it – definitely stands apart from other kinds of fear. Human beings have been preoccupied with creepy beings such as monsters and demons since the beginning of recorded history, and probably long before. Even today in the developed world where science has banished the nightmarish beings that kept our ancestors awake at night, zombies, vampires and other menacing entities retain their grip on the human imagination in tales of horror, one of the most popular genres in film and TV.

In this article David Livingstone Smith, professor of philosophy at the University of New England and director of the Human Nature Project, examines psychological theories in looking to answer the question “Why the enduring fascination with creepiness?”

Bending Mind and Time: 6 of the Best Time Travel Books

I’ve always been fascinated by the use of time travel as a literary device. Matt Staggs begins this brief article with a look at the new book Time Travel: A History by James Gleick, a scientist’s look at representations of time travel in popular culture and science. Staggs then discusses five of the best known novels featuring time travel:

I’ve always been fascinated by the use of time travel as a literary device. Matt Staggs begins this brief article with a look at the new book Time Travel: A History by James Gleick, a scientist’s look at representations of time travel in popular culture and science. Staggs then discusses five of the best known novels featuring time travel:

- The Time Machine by H.G. Wells (1895)

- Kindred by Octavia Butler (1979)

- Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut (1969)

- Outlander by Diana Gabaldon (1991)

- 11/22/63 by Stephen King (2011)

He concludes:

In the absence of the real thing, novels function as time machines in their own right, allowing us to look at what was, and what may yet be, at a safe distance.

RELENTLESSLY RELEVANT: The Dangerous Legacy of Henry James

I’ve long thought that, with the possible exception of “The Turn of the Screw,” the works of Henry James shouldn’t be studied until graduate school. James’s insight into the human psyche is so subtly complex that only people with a lot of life experience can understand and appreciate it.

Paula Marantz Cohen, Dean of the Pennoni Honors College and a Distinguished Professor of English at Drexel University, uses the recent issuance of a stamp honoring Henry James by the U.S. Postal Service as a springboard for this article. Cohen sees James’s “dense and difficult” late writing — The Ambassadors, The Wings of the Dove, and The Golden Bowl, all written between 1902 and 1904 — as a bridge from the Victorian era into modernity (the age of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf) and then, further, into our age of postmodernism:

His superficial kinship was with European modernists like James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, and Virginia Woolf. Late James is often opaque, … and opaqueness was a hallmark of the modernist rejection of facile realism.

…

There is an indeterminacy with respect to truth that his later work supports in such an aggressive way that it becomes a worldview. Words, normally meant to communicate, are deployed more as obstacles to communication than as facilitators to it. The fragmented nature of his dialogue leaves meaning unresolved between characters (he describes them as continually “hanging fire”).

Cohen writes that James’s characters “were always trying to make the most out of situations and see the best in people through their imaginative flexibility — to salvage meaning to some positive, creative end.” However, she laments, in academia this process became subverted into giving truth “purely provisional meaning based on what the speaker wants to relay and the listener/reader wants to hear.” The result “betrays the ideals of [James’s] moral imagination. And yet his great later writing can be seen as its precursor.”

© 2016 by Mary Daniels Brown