Scientists uncover surprisingly consistent pattern of scholarly curiosity throughout history

Sometimes the more things seem to change, the more they stay the same.

By analyzing the recorded interests of thousands of scholars born before 1700, researchers found that intellectual curiosity tends to cluster around three broad domains: the human, the natural, and the abstract. These clusters appear in similar proportions across vastly different regions and historical eras, indicating a possibly universal structure in the way people pursue knowledge.

A.I. Is Poised to Rewrite History. Literally.

“The technology’s ability to read and summarize text is already making it a useful tool for scholarship. How will it change the stories we tell about the past?”

Bill Wasik, editorial director of the New York Times Magazine, examines “how A.I. — one of whose many superpowers is the ability to inhale large amounts of text in an instant and offer credible summaries of it — might transform the way history is written.” The AI in question is NotebookLM, an app developed by Google and tech journalist and historian Steven Johnson. The program uses only files “selected by the user, on the premise that most forms of research benefit from thoughtfully curating your source material.”

Wasik asked several academic historians “How might A.I. change the way history is written and understood?” The use of A.I. to influence and even generate historical writing has tremendous implications for areas such as who gets to tell what stories, whose stories get told, and whose voices get erased from history. These issues increase as A.I. is used to create “cogent-seeming summaries of enormous troves of texts without much attention to their origins or agendas.”

Jung’s Five Pillars of a Good Life

“The great Swiss psychoanalyst left us a surprisingly practical guide to being happier.”

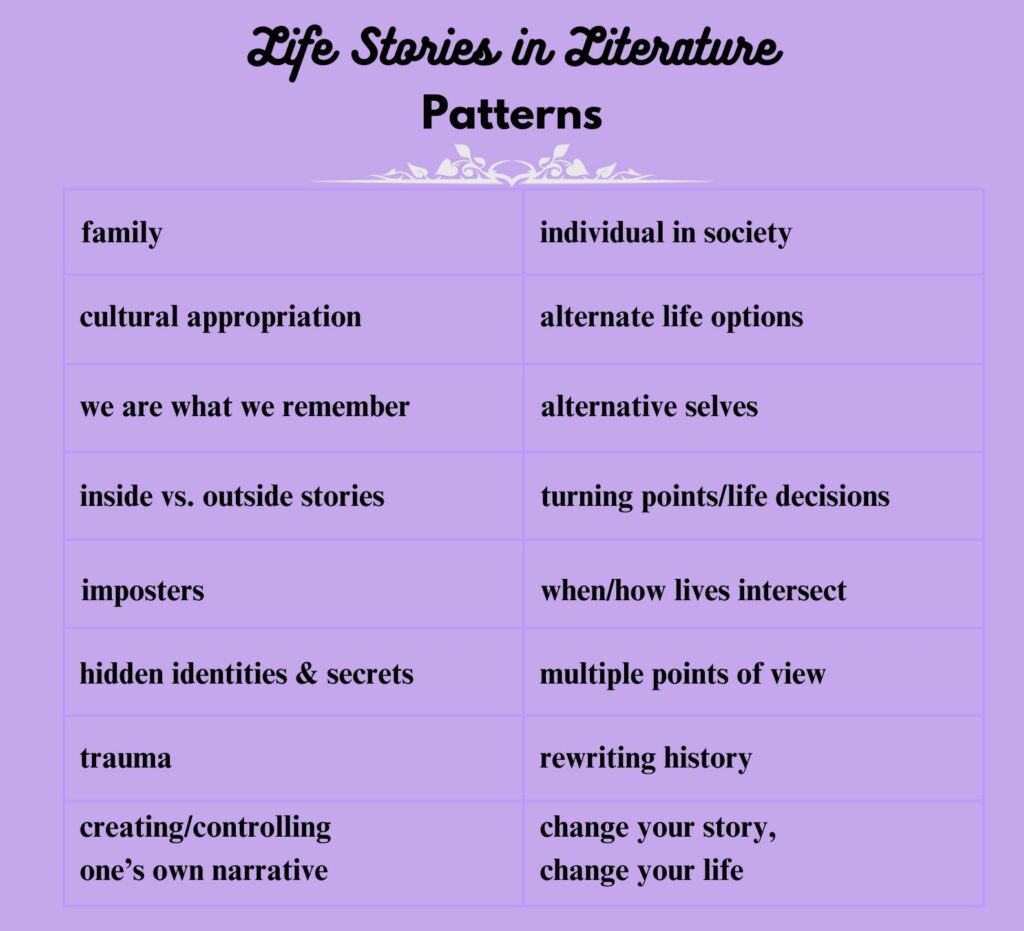

One aspect of Life Stories in Literature is how people find meaning, purpose, and happiness in their lives. Yet how does an individual go about doing this? Who sets up the criteria and standards of “meaning” and “purpose” and “happiness”? Arthur C. Brooks explains Carl Jung’s five pillars of a good life and offers his own seven-point summary.

Why the search for meaning can cause ‘purpose anxiety,’ and what to do about it

“Find your purpose.”

It has become such common advice that few question it. But rather than inspirational, it can feel like a burden. How do I go about finding this and what if I never do?

This is “purpose anxiety” — the gnawing sense that one’s life should have an overarching purpose, but it’s unclear how to discover it.

Alina Tugend consults several scholars on how to evaluate meaning and purpose in their lives in an age when previous thought systems, such as religion and social norms, are dramatically changing and declining.

The Otherworldly Ambitions of R. F. Kuang

R.F. Kuang’s 2022 novel Babel is about the most brilliant portrayal of the relationship between narrative identity theory and culture that I’ve read. In this article Hua Hsu, a staff writer at The New Yorker, visits with Kuang about her recently published dark academia novel Katabasis:

“Katabasis” is an effective satire of academic life. But there are very basic questions that Alice [one of the novel’s lead characters], a brilliant thinker and a rabidly box-ticking student, faces—and they feel like some that Kuang is contemplating herself. “What burns inside you? What fuels your every action? What gives you a reason to get up in the morning?” When Alice’s adviser asks these questions, she doesn’t have any good answers.

The Problem With R.F. Kuang’s Fiction

My problem with Laura Miller, cultural critic for online magazine Slate, is that she usually manages to wring all the life out of the literature she reviews. Here she takes on R.F. Kuang (see article above), whose “abiding weakness as a novelist lies with character,” according to Miller.

Here’s part of what Miller has to say about Babel:

Although the novel has been praised for its political insight, reading it is like being lectured to for hours about things you already know by an indignant 19-year-old who has just taken their first real history class. If you are also 19 and completely unaware of the depredations of the British Empire, perhaps that won’t seem so tiresome. But if not, not.

It doesn’t help that although Babel is set in the 1830s, the novel’s characters all speak like the characters in contemporary YA fiction, a genre that Kuang’s work operates both within and above. Its chapters come adorned with quotes from intimidating-sounding authors like Horace or Dryden that summon a miasma of erudition cloaking the often undercooked elements of the book. As more than one critic has pointed out, the novel’s magic system and its analogy to real-world history don’t make much sense.

I quote at such length here to give the full measure of how Miller is apparently unaware that Babel is an obvious work of fantasy, which is why “the novel’s magic system and its analogy to real-world history don’t make much sense” to her.

Don’t Believe What AI Told You I Said

Yair Rosenberg, a staff writer for The Atlantic, commiserates with prolific science fiction author John Scalzi and others over the way AI allows people to create posts that attribute to them words that they never wrote or said.

Author Nicci Cloke on the power of names and identity

When I had the idea for Her Many Faces – a woman on trial for poisoning four members of a private club, told entirely from the perspectives of the men around her – I started to reflect on the power of names and our sense of identity. I looked back at my career and personal life and thought about the way my sense of myself has shifted and changed, and the impact that other people have had on that.

© 2025 by Mary Daniels Brown