What I Wish Someone Had Told Me 30 Years Ago

Jim VandeHei adapted this article from his recent book Just the Good Stuff: No-BS Secrets to Success (No Matter What Life Throws At You). I give the book’s full title, including the long and awkward subtitle, because it carries the true point: This is not a stuffy, moralizing harangue, but the lived experience of an ordinary guy.

My own life is littered with mistakes. But I learned something from every dumb move and used it to try to get the big things right. Five decades in, that is what matters most to me: cutting myself slack on my daily sins or stumbles so I can focus on the good stuff.

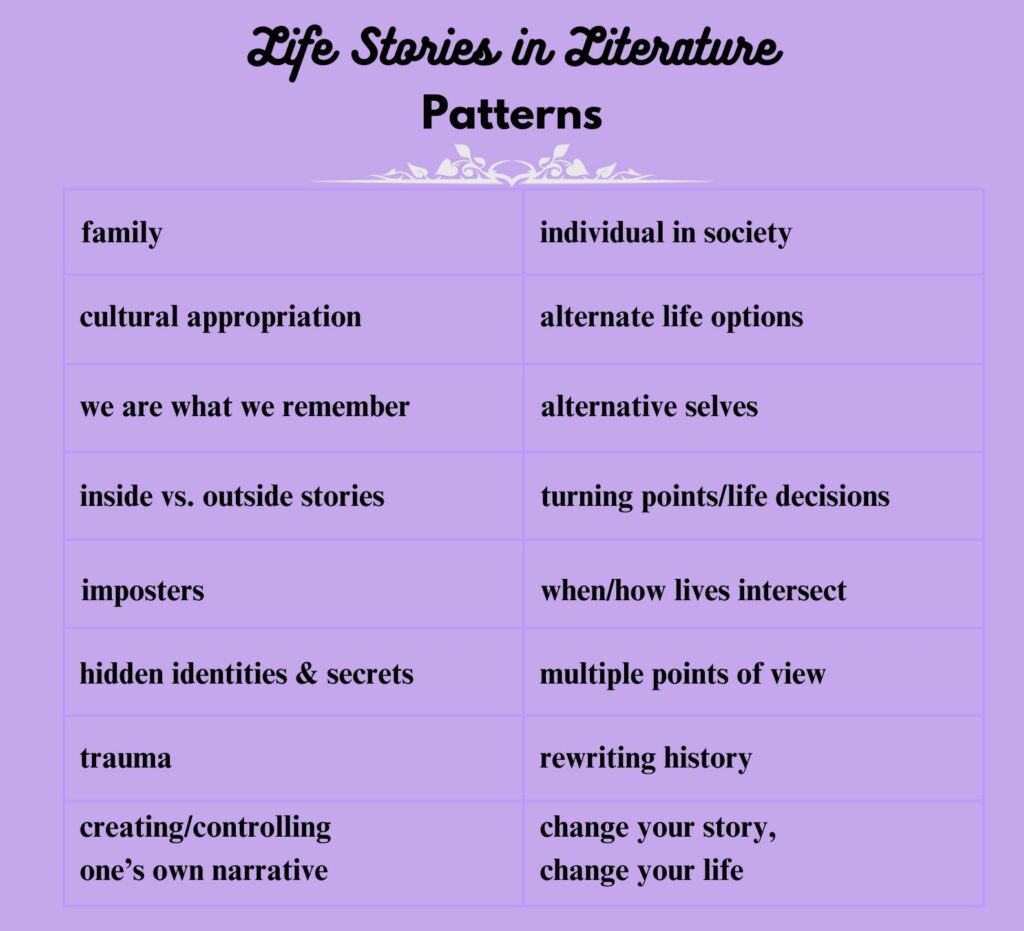

This kind of self-appraisal is one feature of narrative-identity psychology.

Your Memories Are Like Paintings

Because we are what we remember, realizing how we form, store, and retrieve memories aids in understanding how life story theory works. “Memories are not a true or false picture of the past; they are a Monet lily pond,” writes Kevin Berger, editor of the science magazine Nautilus.

Our brains never see the past clearly. They are like painters who are never satisfied. They constantly retouch the past with the colors of the present, putting a fresh version of ourselves on display for us to ponder.

Here Berger interviews Charan Ranganath, professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of California, Davis, author of Why We Remember (2023). Ranganath argues that evolution has enabled our brains “to store only the sensory inputs that matter—the ones that seem new.” Evolution has also programmed our brains to store inputs associated with emotions such as fear, lust, despair, and love: “The more intense the emotion, the more likely we are to remember the experience that caused it.”

Ranganath’s explanation goes a long way toward explaining why some of the strongest human memories are of traumatic events.

Crime Novels with a Sense of Place and Manners

“Peter Nichols on crime stories that could only be set in one place, among one set of people.”

Novelist Peter Nichols writes, “for me, the most satisfying crime fiction are stories that spring from a particular place and the people who live there; a place and manners the author knows well; stories that could not happen anywhere else.” This statement carries an intuitive understanding of the relationship between social context and individual behavior.

All of us are individuals trying to find our place within the society we live in. This explains why we are fascinated by fictional characters who are on the same journey.

‘James,’ ‘Demon Copperhead’ and the Triumph of Literary Fan Fiction

“How Percival Everett and Barbara Kingsolver reimagined classic works by Mark Twain and Charles Dickens.”

New York Times critic A.O. Scott explores two recent novels—James (2024) by Percival Everett and Demon Copperhead (2023) by Barbara Kingsolver—as examples of modern attempts to rewrite original texts that “are both profoundly imperfect books, with flaws that their most devoted readers have not so much overlooked as patiently endured.”

How Members of the Chinese Diaspora Found Their Voices

“In the past few years, many Chinese people living abroad have found themselves transformed by the experience of protest.”

Han Zhang, a member of The New Yorker’s editorial staff, reports on how recently many Chinese people living abroad have banded together to speak up about repressive policies. They have been “[i]nspired by political organizing they saw firsthand in the U.S.—around #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and labor unions.”

What I learned from sharing my private self with an AI journal

For the ‘quantified self’ movement, the dream is better living through data analysis. You know the quantified self disciples: they’re the people dutifully recording their steps, sleep, sex, anything that can be turned into a number, and then gathered and probed using technology to reveal the secrets of health and happiness.

Science journalist Angela Chen tells us what she learned from typing her journal into various AI programs.

What Do 90-Somethings Regret Most?

“I interviewed the oldest people I know. Their responses contradict popular research about aging and happiness.”

This is not by any means a controlled study, but it provides some interesting food for thought. Lydia Sohn, a minister, interviewed several members of her congregation in their 90s about “their fears, hopes, sex lives or lack thereof.”

What she learned contradicted the usual assumptions about older people and life:

Their joys and regrets have nothing to do with their careers, but with their parents, children, spouses, and friends. Put simply, when I asked one person, “Do you wish you accomplished more?” He responded, “No, I wished I loved more.”

‘A rumpled paperback showed me I was not alone’: Charlotte Mendelson, Michael Rosen and others on the books that marked their coming of age

Some enlightening conversations from people interviewed by The Guardian.

Pat Barker on The Silence of the Girls: ‘The Iliad is myth – the rules for writing historical fiction don’t apply’

This article in The Guardian is from 2021, but its content is more important than its age. Pat Barker explains how she came to write The Silence of the Girls, a work that gives voice to the women in Homer’s Iliad.

When Reality Feels Unreal

“Why your life sometimes feels alien to you.”

Every once in a while I come across a situation or plot point in a novel that makes me think “This could never happen.” That’s why I linger over stories like this one that reinforce the adage that life truly is stranger than fiction.

Writer Katherine Harmon Courage talks with Rachael Murphy, who spent years as a medical resident meeting with patients experiencing the sensation that their life doesn’t seem like their own. Courage “wanted to know what is happening in the brain when reality ceases to feel real, what that experience is like, and what that might tell us about the nature of our constructed reality.”

Murphy explains:

When you’re dissociated, the integration of emotional information and the factual information is severed. When you’re in survival mode, you don’t have room for the emotional information. But that’s the information that’s tied to everything you feel and your sense of self.

© 2024 by Mary Daniels Brown