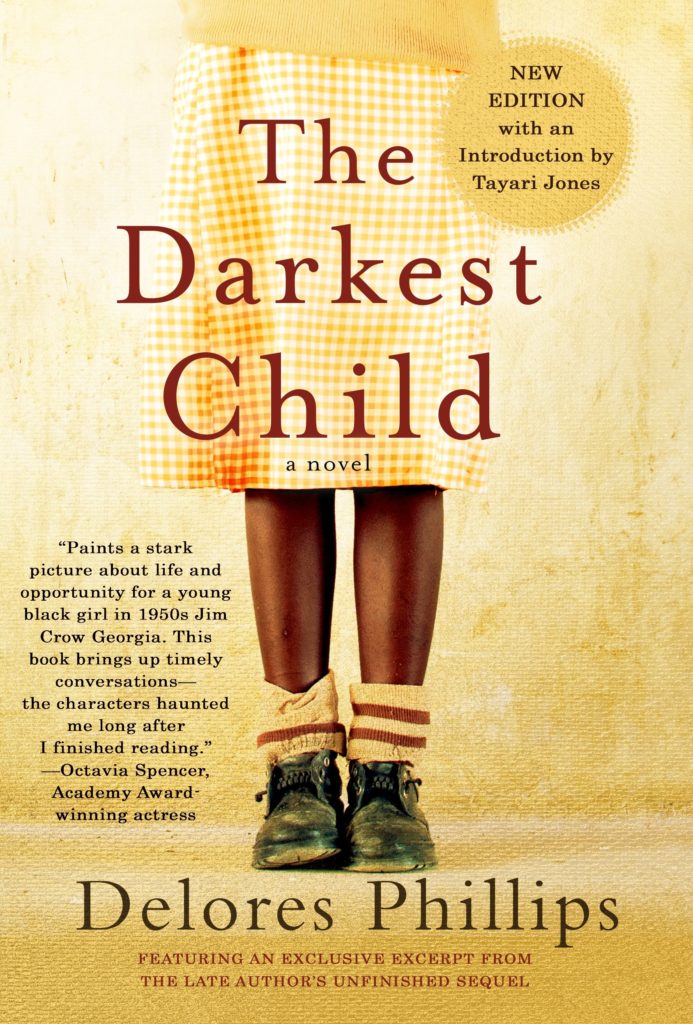

The Darkest Child by Delores Phillips

- Soho Press, 2004

- Paperback, 390 pages

- ISBN 978-1-61695-872-5

Highly Recommended

Review

The Darkest Child is a powerful novel you’ve probably never heard of, but it’s not for everyone.

Set in the early 1950s in rural Georgia in the U.S., this novel presents a picture of life during the Jim Crow era, when formal laws and societal conventions reinforced racial segregation in the South. The story focuses on the family of matriarch Rozelle “Rosie” Quinn, the domineering mother of 10 children fathered by several men.

The first-person narrator is Tangy Mae, the sixth of Rosie’s children, who has the darkest skin and is therefore, in her mother’s opinion, the ugliest. Rosie requires her children to leave school at age 12 and get a job to contribute to the family income. As the novel opens, most of the older children have gotten jobs and found other places to live, though they continue to give Rosie money.

But Tangy has already turned 13 and is therefore in a precarious position within the household. Because of Tangy’s intellectual ability, school authorities have convinced Rosie to let Tangy stay in school. Rosie has agreed, as long as Tangy gets a job, brings home money, and keeps up with her responsibilities at home.

As the oldest child still at home, Tangy cares for her younger siblings. She’s also responsible for meeting her mother’s demands:

In my mother’s house, we waited. We waited on her and for her. We waited for change, and nothing ever changed, except our mother’s moods.

(p. 239)

One such demand is for Tangy to make and deliver her mother’s coffee every morning as soon as Rosie announces she’s ready. Determined to get an education, Tangy manages to fulfill her home obligations while keeping up with her school work.

Rosie’s moods drive the story. She’s a selfish, demanding woman who controls her children through threats and violence. “I thought she [mother] was beautiful, despite my acquaintance with the demon that hibernated beneath the elegant surface” (p. 2), Tangy tells us. And later: “I wondered that day if I was the only one in the room who knew that there was something terribly wrong with our mother” (p. 15).

In a society that provides no safety net for either mentally ill parents like Rosie or her children, Tangy struggles to understand and come to terms with her situation: “I loved her with all my heart, but . . . I was determined to discover from the pages of my schoolbooks how to break the chains that bound me to my mother” (p. 6).

I was baffled by the ambiguities of my mother’s emotions and behavior. She denied and feared God in the same breath. She allowed our actions to shame her, and yet she was void of shame. I truly believed there was something unnatural about her—a madness that only her children could see. My yearning was not to understand it, but to escape it.

(p. 122)

Rosie’s children aren’t the only ones who can see her madness. The whole community fears Rosie, who acts impulsively and then invents her own version of reality. In a key scene, Rozelle tells the sheriff that the infant Judith fell from her arms off the porch. “She was convincing,” Tangy marvels. “I thought for a moment that maybe I was mistaken in what I thought had happened. I thought she had thrown Judy from the porch, but no mother could do that, not even mine. Could she?” (p. 178).

When the civil rights movement finally arrives in town, one of Rosie’s older sons is arrested. This occurrence aggravates Rosie’s psychological instability and provides the focal point of the story. The oldest of Rosie’s children, a young woman called Mushy, has moved to Cleveland and gotten a job, but she comes back to Georgia to help the family cope. Near the end of the novel Tangy asks Mushy why she’s still so afraid of their mother. Mushy replies, “I’m not afraid of her; I’m afraid of becoming her” (p. 308).

This revelation convinces Tangy that a similar escape is her only real option, and the novel ends with her striking out on her own. Delores Phillips intended to write more of Tangy’s story but did not finish it. (See Author Notes below.)

Content Concerns

I avoid the term trigger warnings because I still have mixed feelings about it. However, because I’m highly recommending this novel, I want to give fair warning: Some of the material in this novel is graphic and upsetting:

- physical, verbal, and sexual abuse, some involving young children

- graphic and extreme physical violence

- death of a loved one

- infanticide

- mental illness

- racist language and racial violence

Author Notes

Delores Faye Phillips (September 26, 1950 – June 7, 2014) was born in Georgia. Her family spent two years (1959-1961) in Detroit but returned to Georgia after their father died. In 1964 Delores’s mother moved the family to Cleveland.

Delores trained as a practical nurse in Cleveland. She married Charles Phillips in 1983. He died five years later.

Delores had always wanted to be a writer. She earned a B.A. in English from Cleveland State University in 1994. She began the work that would become The Darkest Child as a long-form poem, but after four years she had written several hundred pages that she then reshaped into a novel.

The Darkest Child was published in January 2004. Phillips worked on a sequel to the novel while continuing to work full time as a nurse. Titled “Stumbling Blocks,” the sequel was unfinished at the time of her death in 2014.

© 2022 by Mary Daniels Brown

This does sound like a challenging novel.