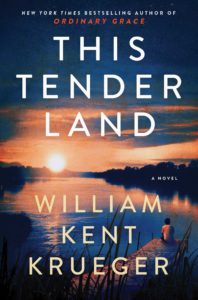

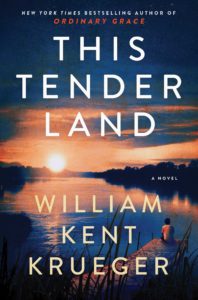

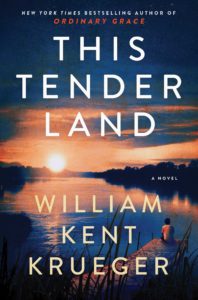

A big-hearted coming-of-age epic

The significance of a life lies not only in the living, but also in the telling. William Kent Krueger brings this truth to literary life in his magnificent novel This Tender Land. Throughout, the voice of the narrator breaks through not only to tell us the story of his experiences, but to emphasize the significance those events had in influencing the rest of his life.

The recurring voice of the narrator is the most salient characteristic of this novel. The storytelling voice gives purpose and moral weight to a book that celebrates the power and beauty of telling life stories.

Krueger, William Kent. This Tender Land

Simon & Schuster, 2019

Hardcover, 444 pages

ISBN 978-1-4767-4929-7

Highly Recommended

Only a great novel can manage to be both chilling and heart-warming. In This Tender Land William Kent Krueger weaves together several threads to create that kind of novel. Set in the summer of 1932, the book tells the story of four orphaned children traveling down the Gilead River in Minnesota in search of the Mississippi River, which they hope will transport them to a better life.

the setting

The novel opens at the Lincoln Indian Training School on the banks of the Gilead River in Minnesota in the summer of 1932.

the four main characters

Odie O’Banion, the first-person narrator, is 12 years old that summer. His brother Albert is 16. The brothers have been the only white children at the school since they were orphaned when their father was killed four years earlier.

Odie and Albert are friends with Moses Washington, called Mose, an Indian. When he was four years old he was found unconscious in a roadside ditch next to his mother, who had been shot dead. Mose’s tongue had been cut out. Odie and Albert know sign language because their mother was deaf, and they have taught Mose to sign.

The fourth member of the runaway group is six-year-old Emmy Frost, the child of a nearby farm family who becomes an orphan when her mother is killed in the tornade that strikes the school just before the boys decide to leave. Emmy, about to be adopted by Mr. and Mrs. Brickman, the couple who run the school, begs the boys to take her with them. They don’t have the heart to leave her with Mrs. Brickman, whom they call the Black Witch, and her husband.

The novel opens with a prologue that sets the stage for the story to follow:

The tale I’m going to tell is of a summer long ago. Of killing and kidnapping and children pursued by demons of a thousand names. There will be courage in this story and cowardice. There will be love and betrayal. And, of course, there will be hope. In the end, isn’t that what every good story is about?

This Tender Land (p. 4)

When the four young people steal a canoe and take to the river, they don’t have a destination firmly in mind. They just know that life anywhere else must be better than the life they’re living at the Lincoln School, where physical punishment and sexual assault are routine occurrences. (Although Odie lets us know that sexual assault occurs, there are no scenes that present it.)

There are three ways to approach this book:

- as a historical novel

- as a quest narrative

- as a coming-of-age story

1. historical novel

The novel opens at an Indian training school in Minnesota, one of many boarding schools in the U.S. created to transform Native children into good citizens. From a young age Native children were sent to these schools, where they learned about Christianity and European-centered cultural and social history and values. Children attending these schools were not allowed to speak their native languages or practice their religious and cultural beliefs. The motto of these residential schools, Odie tells us, was “Kill the Indian, save the man” (p. 42).

In 1932 the U.S. was still in the throes of the Great Depression. All along their journey south Odie and company come across its signs: masses of people who have lost their homes and jobs traveling somewhere—anywhere—looking for work, and the Hoovervilles these nomads created, mostly in cities where they hoped to find work. In contrast to the damning picture of the Indian schools, the novel predominantly portrays these encampments as temporary homes created by desperate but decent people. Nobody in Hooverville has much, but everyone shares what they have with those who have less. Odie even meets his future wife at one of these camps, as the narrator tells us in the epilogue.

On their travels the children also come into contact with another sign of the historical time, a traveling tent-revival troupe led by Sister Eve. At a time when very few people had anything to be conned out of, Sister Eve is more interested in providing soup and bread than in swindling those who attend the meetings. And, having a genuine spiritual nature, Sister Eve recognizes a kindred spirit in Emmy and takes her in.

2. quest narrative

The novel’s journey downstream follows the typical quest motif in which the characters set out in search of something valuable. All four of the main characters attain a much better life than the one they left behind in Minnesota. The quest is particularly significant for Mose, who never learned about his Native heritage at the school whose purpose was to drum the Indian out of him. As he sees evidence of Indian massacres and meets Native people along the way, he begins to incorporate the new knowledge into his sense of identity. And Emmy gets a much more nourishing life with Sister Eve than she would have had with the Brickmans.

The O’Banion brothers also discover themselves on this quest. Albert, who has always had a way with machines, gets to hone his skills at a new job. Odie, the focus character, finds his true identity and, with this self-knowledge, steps into a transformed life.

“I finally decided that maybe what I’d lost . . . was my old self, and what I was feeling was a new self coming forth. The reborn Odie O’Banion, whose real life lay ahead of him now.”

— This Tender Land (p. 91)

3. coming-of-age story

The novel’s main framework, though, is Odie’s coming-of-age story. He leaves the Lincoln School a bitter, disillusioned youngster who has experienced things no child should ever have to see or feel. By the end of the novel, as he turns 13, he has found out about his family background and has learned that not all people are selfish, brutal, and uncaring.

“. . . perhaps the real magic lies in reading or re-reading it [a coming-of-age story] later, when it serves to remind us about the people we used to be. The teenage years are probably among the first where we are really aware of the people we are, and, later, the people we once were.”

— Iza Wojciechowska

At 444 pages, This Tender Land is 56 pages shy of qualifying as a Big Book. But it feels like a Big Book. In fact, it feels like an epic. Both the explicit reference to Huckleberry Finn and Odie’s allusive given name contribute to this feeling. So does the big-hearted narrator, who, after more than 80 years of life, comes back with an epilogue and tries “to understand what I know in my heart is a mystery beyond human comprehension” (p. 439).

“Our former selves are never dead. We speak to them, arguing against decisions we know will bring only unhappiness, offering consolation and hope, even though they cannot hear.”

— This Tender Land (p. 163)

Add This to Your TBR Notes If . . .

- you like the story of a life well lived.

- you like historical fiction that immerses you in another time and place.

- children as main characters (in adult fiction) fascinate you.

- you appreciate a good coming-of-age novel.

- you enjoy big stories and Almost-Big Books.

Update: Reference Notes

June 22, 2021

Discovery of a mass grave at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada, has recently made headlines.

Here’s a news story about U.S. boarding schools for Native American children in Washington state.

If you’re interested in learning more about Indian training schools, Book Riot has compiled the list “Books About Indian Residential Schools in Canada: Nonfiction and Fiction.” Although the list focuses on Canada, the Indian residential school movement was very similar in Canada and the United States.

© 2021 by Mary Daniels Brown