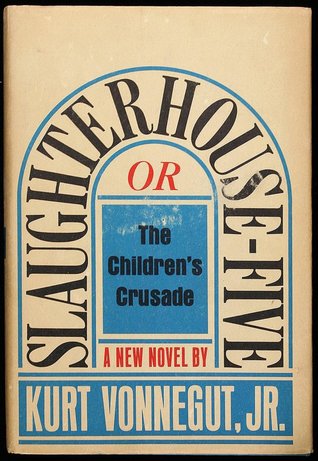

Vonnegut, Kurt, Jr. Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children’s Crusade

Delacorte Press, 1969

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 69–11929

Rereading this book leaves me speechless every time—not because I have nothing to say about it, but because there’s so much to say that I don’t know where to start. Just as the bumblebee flies anyway, this “so short and jumbled and jangled” novel works despite its strange structure.

Rereading this book leaves me speechless every time—not because I have nothing to say about it, but because there’s so much to say that I don’t know where to start. Just as the bumblebee flies anyway, this “so short and jumbled and jangled” novel works despite its strange structure.

In (literary) theory, there are a couple of reasons why this novel shouldn’t work. The first is the mixed point of view. The book’s opening chapter is written as first-person narration, the story of how Vonnegut visited his Army buddy Bernard V. O’Hare in Ohio and how the book got its subtitle. The second chapter begins the story, narrated in third person: “Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time” (p. 20). Most of the book continues as a third-person narration of Billy’s war experiences and his intergalactic travels afterwards. But occasionally Vonnegut breaks back in with a first-person reference to himself as author—a technique known as authorial intrusion—to assure readers that the story he’s telling is the true story of his own experience. Nowadays this mixture of points of view is not unusual, but such overt association between author and narrator was much more uncommon back when this novel was first published.

A second literary quirk of this novel is its mixture of historical reality and science fiction. Billy moves—or rather his mind moves—fluidly between Germany during the war and the planet Tralfamadore, where he is caged and displayed like an animal in a zoo. Science fiction originated as a genre of writing separate from, and considered inferior to, mainstream literature, and its incorporation into a literary novel was unusual for the time.

Yet the continuing popularity of Slaughterhouse-Five exemplifies how theory and application often don’t correspond. This novel works because it stretches to find a way to express the seemingly inexpressible. When Vonnegut delivered the manuscript to his editor at Delacorte Press, he said that the novel is “so short and jumbled and jangled, Sam, because there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre. Everybody is supposed to be dead, to never say anything or want anything ever again” (p. 17).

Rereading the novel recently for a book group discussion, I was struck by how accurately the book portrays PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), which we are now beginning to recognize as a nearly inevitable result of war experience. Here’s Billy Pilgrim’s situation:

Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time… . Billy is spastic in time, has no control over where he is going next, and the trips aren’t necessarily fun. He is in a constant state of stage fright, he says, because he never knows what part of his life he is going to have to act in next. (p. 20)

Later, Billy commits himself to a veterans’ hospital because he fears he’s going crazy. His roommate is Eliot Rosewater, a former infantry captain:

Rosewater was twice as smart as Billy, but he and Billy were dealing with similar crises in similar ways. They had both found life meaningless, partly because of what they had seen in war. Rosewater, for instance, had shot a fourteen-year-old fireman, mistaking him for a German soldier. So it goes. And Billy had seen the greatest massacre in European history, which was the fire-bombing of Dresden. So it goes.

So they were trying to re-invent themselves and their universe. Science fiction was a big help.” (p. 87)

Yet another image suggestive of PTSD occurs near the end of the novel. At an optometrists’ convention Billy starts crying when a barbershop quartet sings, and he doesn’t know why:

he could find no explanation for why the song had affected him so grotesquely. He had supposed for years that he had no secrets from himself. Here was proof that he had a great big secret somewhere inside, and he could not imagine what it was. (p. 149)

A few pages later we learn why the singing had affected him so. Billy was part of a group of prisoners whose German guards took them inside a building when the planes bombed Dresden. When the guards first went outside after the fire-bombing and found the city completely leveled:

The guards drew together instinctively, rolled their eyes. They experimented with one expression and then another, said nothing, though their mouths were often open. They looked like a silent film for a barbershop quartet. (p. 153)

In the end, “there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre.” The best we can hope for is a writer imaginative enough to reach for some way to express the horror of war—a writer like Kurt Vonnegut.

© 2017 by Mary Daniels Brown