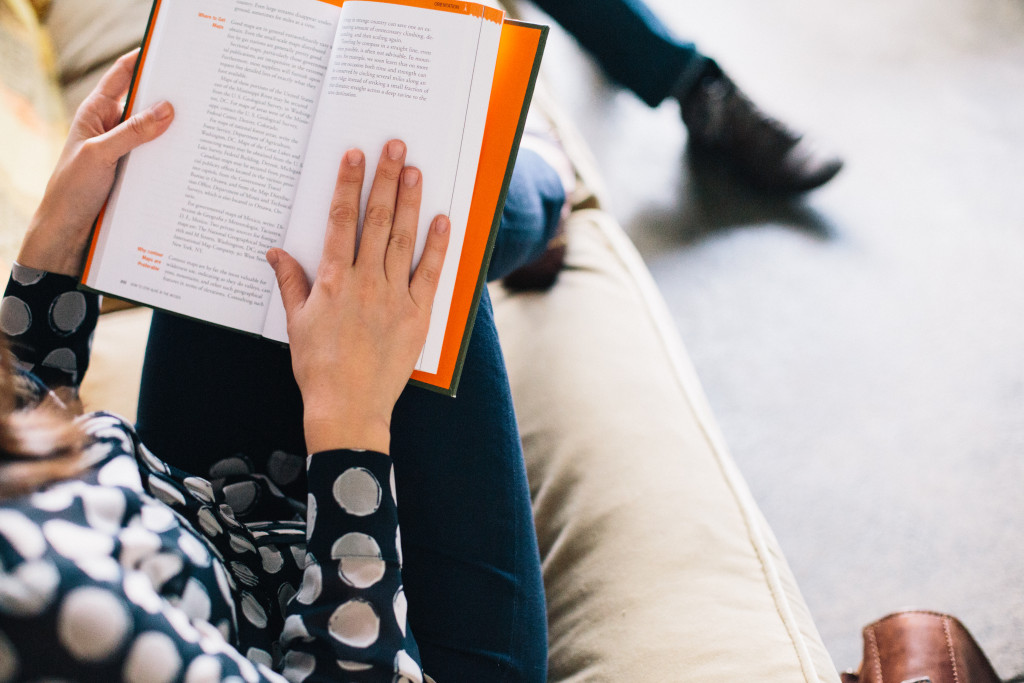

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

Original publication date: 1857

Translated by Lydia Davis

(Penguin Books, 2010)

Highly recommended

Madame Bovary is a seminal work in the rise of literary realism:

Madame Bovary is a seminal work in the rise of literary realism:

an approach that attempts to describe life without idealization or romantic subjectivity. Although realism is not limited to any one century or group of writers, it is most often associated with the literary movement in 19th-century France, specifically with the French novelists Flaubert and Balzac. George Eliot introduced realism into England, and William Dean Howells introduced it into the United States. Realism has been chiefly concerned with the commonplaces of everyday life among the middle and lower classes, where character is a product of social factors and environment is the integral element in the dramatic complications (see naturalism). In the drama, realism is most closely associated with Ibsen’s social plays. Later writers felt that realism laid too much emphasis on external reality. Many, notably Henry James, turned to a psychological realism that closely examined the complex workings of the mind (see stream of consciousness).

Citation: “Realism.” The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia®. 2013. Columbia University Press. 15 May 2016.

Emma Bovary, daughter of a farmer and wife of a country doctor, dreams of a love that she can never attain. In the convent school she attends as a young girl, she reads romantic accounts of mythical love and imagines a similar life for herself. But her visions of what married life should be quickly fade in the face of real life in a country village. She then turns to motherhood to sustain her, but her lofty visions of motherhood pale in the reality of the everyday chores of caring for a child. Still searching, she hires a servant to take care of her daughter and imagines herself involved in truly passionate love affairs that rise above quotidian reality. In a discussion about literature with Leon, one of her would-be lovers, occurs the following exchange:

”That’s why I’m especially fond of the poets,“ he said. “I think verses are more tender than prose, and more apt to make you cry.”

”Yet they’re tiresome in the end,“ Emma said; ”these days, what I really adore are stories that can be read all in one go, and that frighten you. I detest common heroes and moderate feelings, the sort that exist in real life.” (p. 73)

That pesky “real life” always intrudes on the romantic picture of love she developed from her earliest reading:

One day when [Emma and her lover] had left each other early, and she was walking back alone down the boulevard, she caught sight of the walls of her convent; she sat down on a bench, in the shade of the elms. How peaceful those days had been! How she had longed for the indescribable feelings of love that she had tried, with the help of her books, to imagine for herself! (p. 251)

Someone like Emma can never be happy, the novel assures us:

She was not happy and never had been. Why was life so inadequate, why did the things she depended on turn immediately to dust? … Yet if somewhere there existed a strong, handsome being, with a valorous nature, at once exalted and refined, with the heart of a poet in the shape of an angel, a lyre with strings of brass, sounding elegiac epithalamiums to the heavens, then why mightn’t she, by chance find him? Oh, what an impossibility! Nothing, anyway, was worth looking for; everything was a lie. Every smile hid a yawn of boredom, every joy a malediction, every pleasure its own disgust, and the sweetest kisses left on your lips no more than a vain longing for a more sublime pleasure. (p. 252)

Not long after I finished reading Madame Bovary, I came across the article Alain de Botton on why romantic novels can make us unlucky in love. He distinguishes between the tradition of Romantic novels, “novels that do not give us a correct map of love, that leave us unprepared to deal adequately with the difficulties of being in a couple,” and Classical novels, which, he writes, present us with a picture of the right kind of love:

The narrative arts of the Romantic novel have unwittingly constructed a devilish template of expectations of what relationships are supposed to be like – in the light of which our own love lives often look grievously and deeply unsatisfying. We break up or feel ourselves cursed in significant part because we are exposed to the wrong works of literature.

That is exactly what happened to Emma Bovary.

Choose your books wisely.

The Nest by Cynthia E’Aprix Sweeney

The Nest by Cynthia E’Aprix Sweeney

(HarperCollins, 2016)

Recommended

Meet the Plumb children: Leo, Jack, Beatrice (Bea), and Melody. Years ago their father, Leonard, set up a trust to provide them with a little nest egg, “not an inheritance,” he insisted, for a midlife boost. The money was to be distributed when Melody, the youngest child, turned 40. Over the years “the nest” has grown more than Leonard ever imagined. Since Leonard’s death, the fund has been administered by his wife, Francie, who has steadfastly resisted her children’s various pleas to allow them to borrow against their future inheritance.

Until now. A very drunk Leo, the oldest, has picked up a pretty young woman from the catering staff at a family wedding and driven off with her for a quick tryst. Along the way Leo drives into a spectacular car crash that causes the amputation of the young woman’s foot. To keep Leo out of trouble and the story out of the papers, Francie has approved a huge chunk of the nest as a hush-money settlement quietly arranged by Leo’s cousin and family lawyer.

The book opens as the other three siblings gather for a meeting with Leo to make clear that they expect him to repay the nest so that they can all get their money when Melody turns 40 in three months. Over those three months we get to know all four of the Plumb children, two of whom desperately need that inheritance—the whole amount they’ve been counting on, not the half left after Leo’s payout.

Sweeney deftly brings all these major characters, along with a few minor ones, to life in an exploration of the meanings of family, relationships, commitment, betrayal, and money. The resolution, which is exactly right for these characters in these circumstances, is a lesson in moving through dysfunction into a new working definition of family.

A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

© 1959

This book was popular when I was in college back in the late 1960s. I never got around to reading it back then, and the same mass market paperback has been kicking around on my bookshelves ever since then. It won the 1961 Hugo Award for best science fiction novel.

This book was popular when I was in college back in the late 1960s. I never got around to reading it back then, and the same mass market paperback has been kicking around on my bookshelves ever since then. It won the 1961 Hugo Award for best science fiction novel.

A Canticle for Leibowitz is a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel that deals with the themes of recurrent history and of the conflicts between church and state, and between faith in science. It comprises three sections:

Part I: Fiat Homo (“let there be man”)

Part II: Fiat Lux (“let there be light”)

Part III: Fiat Voluntas Tua (“let thy will be done”)

Part I opens 600 years after nuclear devastation, known as the Flame Deluge, destroyed 20th century civilization. Isaac Leibowitz, who had been a scientific engineer with the U.S. military, started a monastic order to preserve as much knowledge as possible by hiding books, memorizing books, and writing out new copies. The order’s abbey in the Utah desert is the repository for the Memorabilia, the remaining documents of the earlier civilization. We learn that after the nuclear devastation, there had been a backlash against the science and technology that had produced it, a period known as the Simplification, when learning, even the ability to read, became a cause for execution. For 600 years the Order of Leibowitz had been keeping safe the Memorabilia for a time when the world was once again ready for it. Part I ends with the canonization of Leibowitz as Saint Leibowitz.

As Part II opens, 600 years after Part I, civilization is beginning to emerge from the previous dark age. While scientists study the Memorabilia at the abbey and begin to make crude instruments from the preserved descriptions, political unrest and manipulation heat up.

After another 600 years, in Part III, mankind once again has nuclear weapons along with spaceships and extraterrestrial colonies. Members of the Order of Saint Leibowitz load the Memorabilia onto a ship and head off toward another planet just as the people of earth once again destroy themselves through nuclear attack.

Through its three sections this novel examines the themes of the cyclical recurrence of history and the eternal conflicts between darkness and light, knowledge and ignorance, truth and deception, religion and science, and power and subjugation. A Canticle for Leibowitz has remained in print since its original publication and is generally considered one of the outstanding works of science fiction. I’m glad I finally got around to reading it.

The Chatham School Affair by Thomas H. Cook

The Chatham School Affair by Thomas H. Cook

(Bantam Books, 1996)

Recommended

I’ve seen so many recommendations of this book, which won the 1997 Edgar Award for Best Novel, that I finally had to read it.

Henry Griswald, now an old man, narrates this story of an event that occurred about 70 years ago, in 1927, when he was 15 years old. In this classic coming-of-age story, he reflects on the significance of the event and how it affected both his own life and the lives of others.

The structure of the novel features a framing device, a short sequence at both the beginning and end, that serves to introduce, then conclude the main action. At the beginning, an old friend visits Henry, now an old man, to enlist his help in selling the property that contains Milford Cottage. At the end, after the sale of the property, the book returns to its present time with a short section in which Henry distributes the money from the sale of the property.

The bulk of the novel, between these two events, consists of Henry’s memory, examination, and explanation of what happened at Milford Cottage on that day long ago. He begins with the most general memories—description of the setting and introductions of the characters involved. He continues to peel back the layers of the experience, like peeling an onion, gradually moving toward the center in ever-tightening circles. This spiraling structure is appropriate, perhaps even inevitable, in the narration of how a character comes to understand how a long-ago event affected the rest of his life.

I recommend this novel for anyone interested in deep psychological fiction.

Year-to-date total of books read: 17